Guest blog: Comparing and contrasting the business models of retailers and brand manufacturers

A wide choice of products at a range of prices across the country remains a good measure of an effective grocery market for shoppers. Retailers and suppliers play distinct roles in delivering this and it is important to understand the differences when considering policy. A refinement in one area may cause harm in another. Here we take a look at the financial models of retailers and brand manufacturers, highlighting their respective strategic priorities and suggesting that a comparison of their financial measures is unenlightening, being a comparison of apples with pears.

The retail model

Historically, the nature of bricks and mortar retailers has been to control the means of distributing fast moving consumer goods, from many branded and own label suppliers, to large numbers of domestic consumers in a concentrated space, in a cost-efficient way.

Small shops developed into larger stores and then into multiples and huge shopping centres like Bluewater. These retail emporia used to guarantee large store traffic and massive turnover often running 365 days of the year.

Retailers have controlled display and promotion in an intimate experience for consumers. That is why so much has been spent on the customer experience and enhancing the retail experience. It has all been about convenience, availability and service at a competitive price. Whether the consumer products concerned are food, electronics, durables or clothes, the principle is the same.

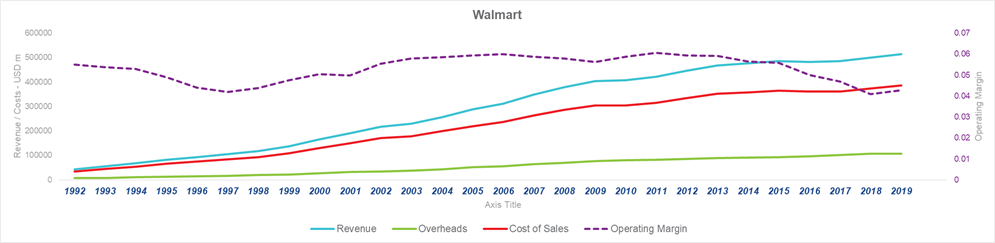

Traditional retailers have relied on high footfall and high spend with modest gross and net margins but with very large turnover. Fixed costs include, distribution, staffing, heating, lighting, rent, rates etc., all of which can be very high in absolute terms, so traditional retailers are highly geared in an operational sense. If they don’t keep the financial wheels turning and hit a certain level of turnover, they won’t even break even. If they don’t make enough to cover all these high operating costs, they rapidly fall into operating losses. This highlights the predicament of retailers in this Covid world.

While they may make relatively small margins on turnover, if they can keep absolute turnover high then the absolute margin they make can be financially attractive. This is known as high stock turn or high operational gearing. High stock turn leading to higher overall turnover at relatively low margins can still add up to a good return on capital employed at the end of the day, in a normal world.

The problem with retail is that if store traffic drops, if stock doesn’t turn over fast, if operating costs rise even a few percentage points, the whole business model goes haywire.

In the 1980s and 1990s Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda, Safeway and Morrisons were locked in a vicious grocery retail price war. Prices were driven down in the battle for market share and all small players were crushed. Aldi and Lidl created the same conditions with the same results.

At that time net margins on turnover decreased to no more than 2-3%.

When the price war was over and many competitors had been rationalised, the surviving players had achieved close-to-dominant market shares. By the 2000s Tesco had acquired over 30% of all grocery retail spend and it was often said that 1 in every 7 pounds spent in the UK went through Tesco tills.

After that price war the major players focused more on quality and novelty rather than just on price. As a result net margins on turnover rose to as high as 7-8%. Tesco and the others became very profitable and highly valued in the stock market.

What Tesco shareholders cared about most was the absolute return on their invested capital not the percentage net margin on sales.

So the managers of Tesco, and similar retailers, aimed:

1) to relentlessly drive down prices, stimulate customer loyalty and generate higher turnover,

2) to attack all operational costs, thereby boosting net operating margins on higher turnover and thereby drive up absolute net profits,

But also…

3) to drive down the amount of capital employed in the business so that percentage returns on capital increased. If you make the same amount of net operating profit with lower capital employed, you are achieving a higher return on invested capital which is bound to please shareholders!

In a vulgar fraction, quite an appropriate term in relation to down and dirty retailing, the higher the numerator (the net profit) and the lower the denominator (the capital employed), the higher the magic Return On Capital Employed (ROCE) percentage.

In pursuit of objective 1), retail buyers became notorious for driving hard bargains with all suppliers. I am sure this would be regarded as an understatement by many fresh produce and packaged goods suppliers to companies like Tesco. Low prices, free product, slotting fees, volume discounts, co promotional discounts, in-store advertising, retrospective discounts were all part and parcel of the purchasing function’s role to reduce prices, pass operating costs to suppliers and improve net margins.

In pursuit of objective 2), retail managers sought zero hours staff contracts, minimum wages, imported labour and reductions in all costs per square foot.

In pursuit of objective 3), directors of retailers made strategic decisions to sell their freehold properties, take capital out of the balance sheet and lease instead. This worked well for decades but backfired when rents and rates rose in recent years. Many retailers have been forced to renegotiate and restructure and they are all lobbying for business rates reductions.

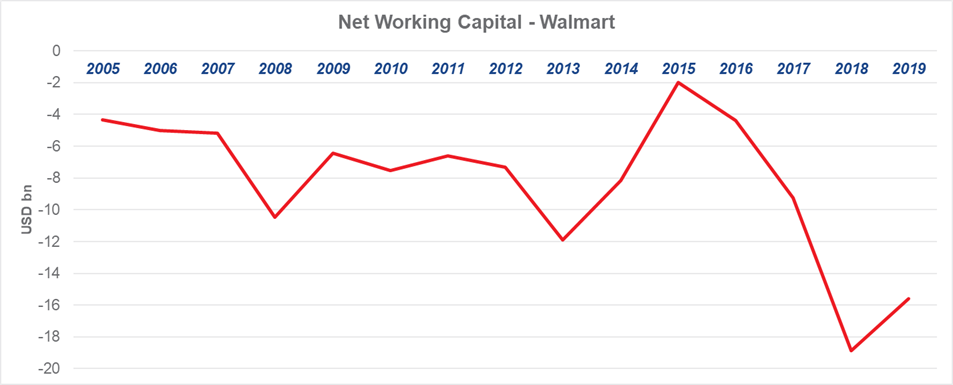

They also sought to reduce working capital by demanding that suppliers retain ownership of stock right through the supply chain to the store shelf, thereby cutting the cost of stock and debtors on their own balance sheets. Taking this one step further, they have charged cash, or immediate credit card payment, for the products to customers but then paid the suppliers on 30, 60 or even 90-day terms. They effectively trade with no stock or debtors but hold the cash receipts until settlement.

These techniques to reduce capital employed can sometimes lead to very odd-looking balance sheets. It is quite normal for a grocery retailer to operate with ‘negative working capital’. This means suppliers are effectively lending their retail customers free working capital.

In a ‘normal’ manufacturing company there will be stock, work in progress, debtors and cash as assets employed, with some creditors reducing the need to fund all the short-term assets required to operate. The need for ‘working capital’ grows as a business grows and is normally financed by shareholders or by banks. This often creates a forceful squeeze on manufacturers as they grow.

But in the case of highly sophisticated retailers, there is no stock (because the supplier is left funding it), there are no debtors (because customers pay immediately), there is limited need for cash and there are usually huge creditor balances, meaning that suppliers fund the retailers balance sheets!

So, looking at a retailer’s balance sheet, it may have virtually zero property assets (because all stores are leased) and no working capital but large credit balances to suppliers and cash sitting around with nowhere to go except in dividends! At least that is how the retail business model is meant to run and for several decades did run.

But the wheels have come off in the last decade mainly because of the internet, online retail and discounters. The likes of Aldi, Lidl, Ocado and Amazon have cut the number of consumers going into retail stores. With lower overheads and costs, they have stripped demand from traditional bricks and mortar retailers. This means reductions in turnover, further pressure on margins and net operating profits falling. Meanwhile, the fact that online retailers have lower business rates and pay lower taxes has created a perfect storm for the retail business model. It is not surprising therefore that many retailers have gone bust in all retail sectors over the last 5 years. Company Voluntary Arrangements are at an all-time high.

In sum, the key KPIs in a retail environment are:

1) absolute turnover (measured year-on-year)

2) customer footfall and average spend (ideally high and rising)

3) gross and net operating margins (ideally low as long as turnover is high)

4) creditor payment days and funding (ideally as high as possible)

5) tangible property employed (ideally very low)

6) working capital employed (ideally negative)

7) return on capital employed (ideally high)

The virtuous circle for retailers can lead to very high shareholder returns but, because of the high operational gearing, the retail business model can lead to rapid losses and financial ruin, as we are witnessing every day at the moment.

By contrast…

The brand manufacturer model

Branded manufacturers have an entirely different business model from that of the retailers that sell their products.

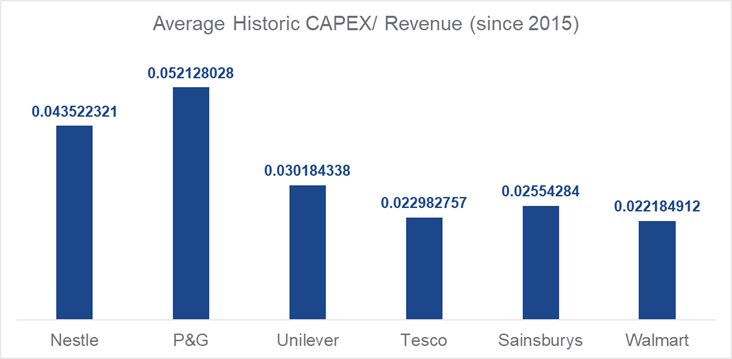

First of all they have to spend significant amounts on research and development and trialling new products.

If and when they create an original, innovative idea, they then need to protect their recipes, designs, packaging and propositions against copies, whether from other branded manufacturers or retail own label.

This means that they have to spend extensively on lawyers and trade mark agents to put in place trade mark, copyright, design and know-how protection.

On top of this, the most interesting and innovative branded products will get nowhere without robust marketing and communication to stimulate consideration, trial, repeat purchase and loyalty from consumers. This is notoriously expensive and difficult, explaining why many new fast-moving consumer goods products do not last beyond a year.

It is rather like pharmaceutical companies that spend fortunes creating a pipeline of blockbuster drugs. Many fail before the blockbusters boost profits and overall returns.

If the new products succeed, the manufacturer then has to invest in production and distribution, raw materials, stocks and working capital.

In the case of manufacturing capacity, it has an annoying habit of coming in discreet steps. Overall fixed costs rise step-fashion as new manufacturing, warehousing or distribution facilities come on stream.

So branded manufacturers have to take significant investment, development and roll-out risks, often with low odds of success.

There are many examples in the branded food sector where retailers wait until the product and brand have been developed and customer demand has been well and truly established before taking the risk of stocking the new product.

Ambient fresh soup (Covent Garden Soup), Organic Chocolate (Green and Blacks) and Fruit smoothies (Innocent) are just three product brands that created entirely new categories which made the hard yards before widespread adoption in supermarkets, rapidly followed by me-too brands and own label knock-offs.

Just as Pharma companies need to achieve good margins on the successful innovations, food companies need to achieve the same for their brands.

One of the difficulties for branded manufacturers is that powerful retailers often expect full disclosure of cost structures so they are aware of the margins being made. They may take the view that more than x% margin would be excessive and either drive down price or demand other contributions to the retail margin.

United Biscuits is a good example of a once proud British biscuit and cake brand manufacturer which battled for years to widen its margins to reinvest in new products and long-term brand-building but was hamstrung by retailer pressure on its margins. In the end it went private in a venture capital deal.

Margin pressure on manufacturers is compounded by the need to finance debtors. This is the flip side of retailers demanding significant credit to fund their negative working capital balances and can be a financial killer for weaker companies.

The ideal scenario lies with companies like Mars, Unilever and Kellogg’s which invest heavily in new product development, brand investment and IP, strengthening their negotiating position versus retailers.

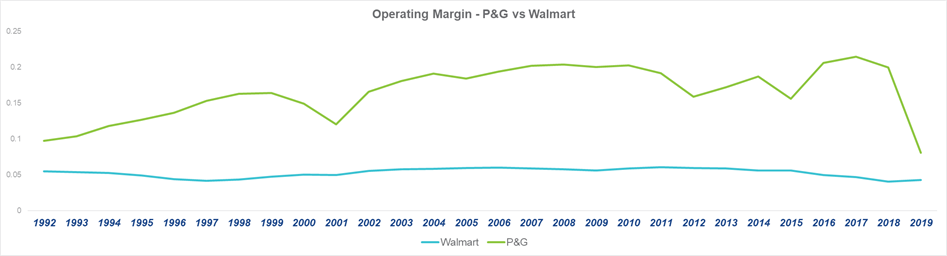

In terms of financial ratios, it is fair to say that strong, innovative and well-resourced brand manufacturers achieve higher net margins than retailers, despite heavy investment in innovation and marketing. In fact, the latter ensures the former. Meanwhile new players and weaker incumbents often display much lower margins because they have been caught in a financial vice.

One way out for some is the willingness to produce own label products side-by-side with their own branded products. Most branded manufacturers are reluctant to do this and indeed some global players say they will never produce own label because it tends to cannibalise their core business model.

However, if a manufacturer has built production capacity but has not yet built volume to fully utilise it, it may have no alternative but to capitulate to own label to offset its fixed costs on the installed capital.

One key performance indicator for branded manufacturers is capacity utilisation in its factories. It is all very well making a 15%-20% net profit on a branded line but not much use if the factory is running at 25% capacity and the company is losing a fortune on under-utilised capital investment.

So, for branded manufacturers, indicators of financial and business health include:

1) high and rising turnover

2) high gross and net margin with low price discounting

3) high percentage of turnover reinvested in innovation and marketing to create loyalty and competitive edge

4) significant percentage of turnover made up of new products and brands

5) high factory capacity utilisation to cover high fixed manufacturing costs

6) well-managed and minimised working capital

Summary

So when considering retailers and manufacturers it will be seen that their business models are quite different. In many ways they are mirror images of one another.

To the extent that retail margins rise, manufacturer margins may decline. To the extent that retailers are being funded by their suppliers, the manufacturers are those suppliers and their working capital may rise out of control.

They work together in a symbiotic relationship, but frequently the retail monoliths win. Only the strongest branded goods manufacturers can maintain their key performance indicators to satisfy shareholders.

The pressure on traditional retailers as direct online selling grows can only put greater pressure on manufacturers’ margins and terms of trade. This is why the relationship is frequently one of love-hate. It certainly makes little sense trying to compare their KPIs.

Both seek to maximise profits and minimise capital employed but the two players get there by quite different routes and the resulting financial indicators are usually quite different.

David Haigh is Chairman and CEO of Brand Finance plc. More information on Brand Finance, a leading international brand valuation consultancy, can be found at brandfinance.com.

Click here to email this to a friend, or share via using the social buttons below: